Fresh from my undergraduate studies in 2012 at Ghana’s University for Development Studies, I still knew so little about the ‘real world’ of development work despite studying development. Like many of my colleagues, I envisioned a white-collar job; sitting in a posh air-conditioned office with a fancy laptop, typing away important stuff all geared toward ‘saving’ some people somewhere.

The above perception was not in a vacuum: in my community, we often saw and were mesmerised by smooth-oil-skinned development workers cruising in land cruisers, in the NGO world. To many of us that was our final destination.

Hence, you can imagine my surprise, when it was time for national service (one-year of mandatory work for tertiary graduates in Ghana) in 2012. I was posted to teach English in a junior high school in a rural mining community in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana called Nkasiem. This brought me face-to-face with real issues like poor quality education, degradation of the environment by small-scale mining, and horrible water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) conditions.

After working for almost five years in rural development on WASH and social protection activities, I went back to school for my graduate studies at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). This allowed me to network with fellow students and delve into relevant academic discourses which helped me reflect deeply on my work. Notable influences include Robert Chamber’s work around putting the ‘last first’ (Whose Reality Counts?); John Gaventa’s Power Cube for analysing power; and Stephen Devereux work around social protection; these really helped me learn and unlearn.

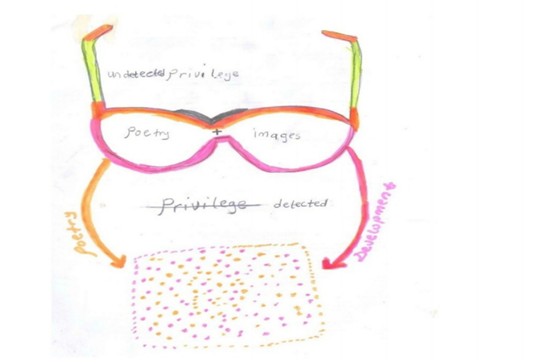

Detecting my privilege

As a development worker, understanding that – being from the city, having a degree, having a job – are all privileged positions providing me with some economic and social power; this is the first bridge to cross.

For example, I was in a village, training women on basic numeracy skills to enhance their shea nut picking business when I noticed a young boy waiting around and watching; he was counting along with me. I was immediately concerned that he wasn’t in school; I questioned his father and lectured him on the numerous benefits of education. But the father simply pointed down to his legs, and then I noticed that he was an amputee; he explained that his son (the firstborn) was the only help he had. The father knew his son had to be in school yet the decision to have his son at home for farming was a matter of survival. I later learned that the man was widowed and one of the poorest in the village. To a development worker from the city, it might sound illogical, but to rural poor folks filling the bellies comes at a great opportunity cost.

In another example, I was in a community registering people on the Ghana National Household Registry (GNHR) under the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (MoGCSP) which sought to register the poorest households into a general database for government support. Upon interaction with some women, I noticed that they preferred to walk miles over a water bridge to access health care for their babies even though there was a much nearer private place. I was immediately concerned about the risks during the rainy season and told them so. To them, they preferred to take that risk because they explained that the services of the distant place were far superior and less costly.

These examples and many more are pointers to tell us that development interventions ought to be designed with the people it is intended for. Thus a health post nearby does not necessarily mean that women would take their babies there nor would a beautiful looking school building ensure that all children are in school; some rural schools may lack teachers and learning materials.

And more critical is the fact some interventions/activities may indirectly exclude people.

Addressing privilege and exclusion

Drawing and poetry proved to be helpful tools for reflecting on my privilege as a development worker. Unchecked privilege can hinder the impact of work in communities. During a course on reflective practices at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) in 2018, I used the opportunity to reflect on many instances in my development work. This has allowed me to put my assumptions aside and think deeply to understand better when I interact with community members, especially those who are frequently excluded from community discussions. This has helped me a lot, as it has made me put people at the centre of my work.

I have written a short Practitioner Voice story which outlines how I work with communities in Gushegu to ensure that Fulani nomads are included: Inclusion of Fulani nomads in WASH programming in Gushegu, Ghana

Hence, as a development worker, I have learnt to:

- Take a step back and reflect, look beyond what I see, interrogate things further, probe and not assume.

- Understand and examine my ‘privilege’ as a development worker.

- To insist on inclusion; for example, during previous activities, we insisted on bringing the Fulanis nomads to the meeting before we could start activities. Community members readily called them to join in.

- Listen to all sides of the story – not just one side. It is important to hear all the different perspectives and needs when designing and implementing development interventions.