These reflections have been provoked by two occasions. The first was in late September/early October last year in India, the Mahatma Gandhi International Convention on Sanitation. The second was AfricaSan5, the fifth biennial African Conference on Sanitation in Cape Town in February this year. The contributions to global warming of these two occasions will have been enormous. For myself, I feel guilt, having been to both. Let me fondly hope this blog leads to good actions which at least marginally offset the impact of my flights. Please read what follows, reflect, and if you agree, do something!

MGISC: Celebrating political leadership in sanitation

The MGISC was remarkable. Ministers of Sanitation and other senior figures from over 50 countries, many of them in SubSaharan Africa, came to Delhi to learn about the national campaign to make India ODF (open defecation free) by 2 October 2019. The Secretary General of the UN came and spoke. The background was that in 2015 Prime Minister Modi had launched the Swachh Bharat Mission Gramin (clean rural India campaign). This meeting was a celebration of its achievements emphasising for other countries the importance of sustained and conspicuous political leadership in sanitation campaigns. This message certainly got across. What the Ministers and others did or were able to do on return to their countries is another question which remains to be answered.

AfricaSan: weaving technical and social concerns together

For its part, AfricaSan5 was held in parallel with FSM5 the fifth international conference on Faecal Sludge Management. With more and more toilet pits needing to be emptied in rural areas and with growing urbanisation, FSM has become a major, even an emergency issue. Having the two conferences running in parallel allowed cross-learning though the FSM preoccupations were more technical and private sector while those of AfricaSan were more social and related to Government and civil society.

Cross-fertilisation- what can India and Africa learn from each other?

Having been at MGISC I went AfricaSan with questions for those African ministers who had been at MGISC: what had they been able to do? Had MGISC made any difference? What of practical and policy use had African Governments learnt from MGISC in India and also what could India learn from African experience? I was planning to see whether Ministers could meet and share problems and progress. But this was not to be. Ministers were not present at AfricaSan, it was said because the South African Government had protocols for visiting Ministers which would have been too demanding and costly with so many of them, so AfricaSan had only Deputy Ministers and others.

Still, the question was and remains: what can African countries learn from India? Even sceptics about the numbers reported in the SBM-G concede that there have been remarkable changes in both infrastructure (toilets) and awareness. Earlier, between the censuses of 2001 and 2011, the number of households defecating in the open actually increased by over 8 million as population growth outstripped toilet construction. This is now tragically happening in some countries in Africa, and the sheer size of some countries, Nigeria stands out, cry out for action. So how did India achieve such a dramatic turnaround? Let me give my view, and my sense of lessons for African and other countries.

1) Administrative leadership

The first factor has been continuity of sustained leadership, not just political at the highest level, but also administrative. This is well understood in Zambia, where Chief Macha and others inspired by him have been outstanding. But the Indian example stands out for sheer scale and intensity. Political leadership has been basic and conspicuous. Less visible and absolutely crucial has been the drive of an exceptionally able and energetic Principal Secretary with a time-bound contract and who has had full political backing. He mobilised an impressive team working in Government. This included around 500 young professionals recruited through Tata Trust funding who were dispersed throughout the country, again not conspicuously visible but in my judgement with significant impact.

2) Resources

A second lesson is resources. It is a repeated refrain that African governments need to allocate their own, not just donor, budgets to sanitation. But this is not a simple equation. An over-generous budget can be a curse as well as a short-term blessing. It is a short-term blessing because it can fund many activities, but it can be a curse through corruption and through dependence on external funding instead of local initiative and ownership. With less funding, African Governments have to go slower than India but this can give space to be more participatory, with outcomes that are more locally owned and crucially more sustainable.

3) Creative campaigns

A third lesson is to provoke, generate, recognise and share many approaches and initiatives in a campaign. Local creative pluralism is key. Children can play a central part through many activities, writing essays, art, theatre, persuading their parents, holding marches and rallies and competitions, and more. Women and women’s groups have proved powerful in India. So has the inclusiveness of drawing in all government departments and the media in many forms and ways, the private sector, civil society, professional associations and others. Actively encouraging, recognising and rewarding local creativity and mutual learning between districts can be synergistic.

4) A warning

The final lesson I would add is a warning. We know from all over the world that urgent targets may galvanise but also generate inflated reporting. The more intense and public a campaign, the more liable this is to happen. In India there is debate and disagreement over divergent findings of surveys which give different statistics for toilet coverage, and also for usage. The current campaign counts numbers of toilets constructed, and numbers of villages, blocks, Districts and even States, declared ODF. Declarations that Blocks, Districts and States themselves are ODF became matters for competition, recognition and reward. It would be contrary to worldwide experience if the competition between Districts, in which the administrative heads, the Collectors or Magistrates, are held responsible for leading the programme, had not led to premature and inflated claims. Immersive research, staying in villages, and de-biasing visits which systematically go to places otherwise unlikely to be visited, do indicate this. There are also unresearched questions whether, when there has been such a massive high profile campaign, there is confirmation bias as people responding to questionnaire surveys are more aware of expected ‘correct’ responses.

Turning short term ‘failures’ into long-term successes

There are nuances here too. In terms of sustainability, local ownership and quality of toilet construction, accurate and honest reporting may have high payoffs in the longer term. Similarly, acting on unwelcome feedback from research rather than ignoring, delaying or suppressing it, should bring greater effectiveness. These are lessons from Madhya Pradesh. There, a Block Development Officer who at least three times reported that he had not been able to achieve his targets, and who learnt about and shared lessons about what was not working and why, was not penalised but promoted. He now occupies a senior and influential position in sanitation in the State headquarters. Madhya Pradesh has also supported immersive research and taken on board its quite negative findings. It may be no coincidence that surveys which compare States suggest that Madhya Pradesh has achieved larger percentage increases than any other major Indian State. That said, African Governments, after earlier quite wild targets in some cases, appear to be grounded in greater realism, with lessons from which India could learn.

There have been follow up visits to India, for instance by Nigerians. Such visits can be valuable but like all of their genre, are vulnerable to impressions from special communities, seeing special things, and meeting people who have been briefed about what to show and say.

Beyond India: Learning from the rest of the Asia region

African governments might do well now to learn also from India’s neighbours Bangladesh and Nepal, which they resemble more. Whereas India is cursed by an individual household toilet subsidy which fuels corruption and dependence, Bangladesh has only had limited and very selective support for those most in need, and civil society, most notably the astonishingly large, omnipresent and effective NGO BRAC, and has empowered women, these all with high level government support over decades. Nepal similarly has had the benefit of a long-term programme, and a policy of no individual household subsidy. And in Nepal, CLTS in its full form has been quite widespread. And also similar to many African contexts, communities in both Bangladesh and Nepal tend to be relatively small and homogeneous. Future visits and sharing could be between African countries and Bangladesh and Nepal, with mutual horizontal sharing and learning.

African lessons for India

What can India learn from African experience? First, the value of grounded reporting. After a phase of unrealistic targets which were drastically scaled down, numerous African countries appear now more grounded in realism. Second, the advantage of no widespread subsidy for individual household toilets. This has allowed space for CLTS, but abandoning the subsidy is not politically feasible in India.

A third lesson is more original, pointing to an opportunity to confront an almost uniquely Indian problem. A striking event at AfricaSan5 was a competition between sanitation workers. Teams of two from different locations within South Africa and neighbouring countries were timed for how long they took to complete a cleaning task. They had to don full protective clothing, and then empty and dispose of waste, not actually faecal but similar, and then remove their clothing and conclude hygienically. What came across was their competence, pride and professionalism, and also the full protection and cleanliness provided by their clothing and equipment. In India sanitation workers come from the lowest castes and are regarded by others as ritually unclean. Many fight against this, but the prejudice and discrimination persist. Could States in India mount sanitation worker competitions like these, and could they be seen repeatedly on public occasions and in the media? Can anyone pick this up and make it happen? So that there is general public awareness of how professional, hygienic, clean and a matter of pride sanitation work can be?

A final challenge

Let me pose a final challenge, to myself as well as others. One breakthrough in the SBMG in India has been senior figures and Bollywood stars entering toilet pits where shit has dried out and matured for a year or more to become harmless and valuable fertiliser. They have then shovelled some of it out. Could they, we, go a step further, don protective clothing, and be taught by sanitation workers how to clean out septic tanks or perform other similar tasks?

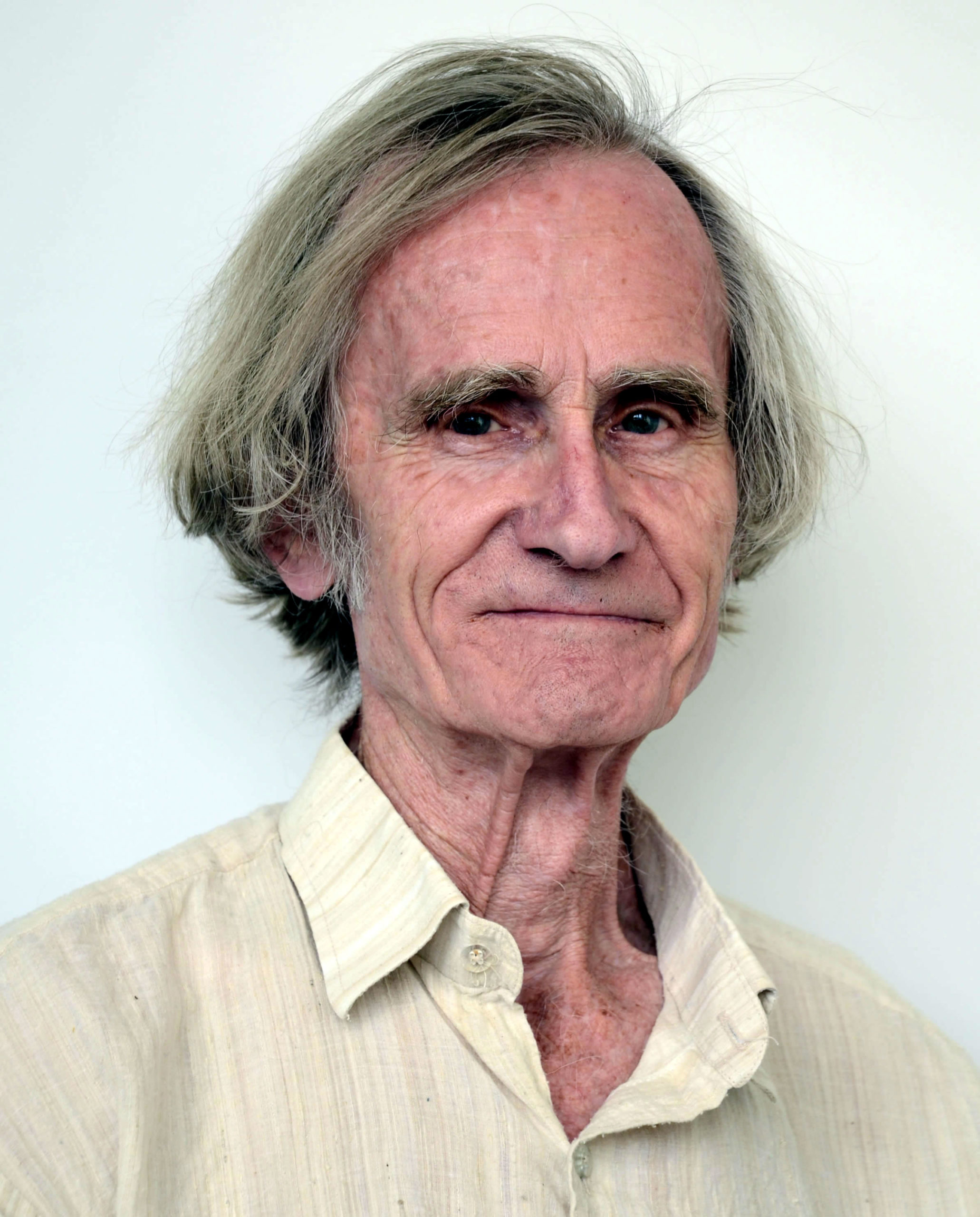

Robert Chambers is a Research Associate at the Institute of Development Studies, UK and a team member of the Sanitation Learning Hub.