How do you get nearly half a million people to stop defecating in the open? This was our challenge from 2009 to 2013 working with post-conflict returnees on sustainable sanitation and hygiene in the district of Gulu in northern Uganda.

Background to the conflict

People from northern Uganda held the majority of the leadership positions in the national government before it was overthrown in 1986. Following this ousting, mostly southern and western Ugandans took up leadership positions in the new government. The people of northern Uganda became particularly concerned that the new government would seek retribution for the atrocities committed by the leaders of the previous government. As a result, a rebel group called the Lord’s Resistant Army (LRA) emerged. The rebel movement tried to recruit but struggled to maintain good regional support in the north. So, the LRA quickly started a trend of self-preservation, characterized by stealing supplies and abducting children to fill their ranks.

Civilians suspected of supporting the government or forming self-defense forces had their ears, lips and noses hacked off by the LRA. During attacks on villages, rebels carried out mass abductions of children who in turn were forced to carry out future attacks – making them both victims of the conflict and perpetrators. The war, lasting for nearly 20 years, led to countless deaths, abduction of close to 20,000 children, widespread human rights violations, the destruction of social and economic infrastructure and relevant to this story, the displacement of close to two million people.

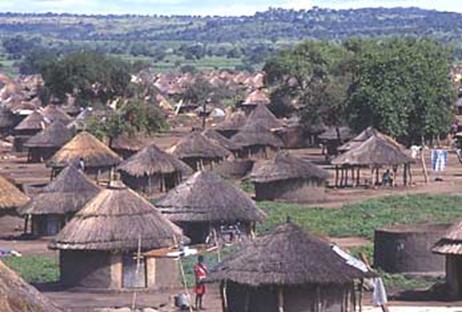

From 1996, the Ugandan government, unable to stop the LRA, required the people of northern Uganda to leave their villages and enter government-run camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs). This was to deny rebels the chance to loot food and abduct civilians for recruitment in the force. Although these camps were created for the safety of the people, they were rife with disease and violence. At the height of the conflict, 1.9 million people lived in these camps across the region. The conditions were squalid and there was no way to make a living.

The internal displacement of the people of northern Uganda attracted attention and support from many international and local governmental organisations. Relief agencies provided food items, clothes, facilities for making household sanitation like moblets (plastic material that serves as superstructure for latrines to provide privacy), cement, iron sheets and safe water sources among many other things. Many children were born and raised in the IDP camps.

In August of 2006, a Cessation of Hostilities agreement was signed by the LRA and the government of Uganda. In 2007 hundreds of thousands of people left the IDP camps to return home, a place they left many years back. Having been in the camps for so many years relying on relief, some were so dependent that they didn’t want to leave the camps. When they returned to their place of origin, there were high levels of poverty and dependency.

Challenges in accessing sanitation and hygiene

The war displaced all people in rural areas of northern Uganda: the majority of the population of the district. In 2008 the government of Uganda came up with a plan to support transition, including a comprehensive peacebuilding and development plan for the region, the Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP).

Material support for improving household sanitation was not given priority in the plan because it was thought that the IDPs would use locally available free materials to construct traditional pit latrines. During pre-displacement, the population used wood, mud and wattle and would roof their latrines with grass to make superstructure for their traditional pit latrine. When they returned to their villages, they were expected to resume using these materials to construct latrines, drying racks and other items that improve household sanitation.

However, sanitation improvement was not a priority for returnees, even though the materials were freely available, as there was little or no financial support to improve household sanitation. Instead, many demanded the subsidies for latrine construction they received when they were in the camps. Those returnees born and raised in camp settings did not have latrine construction skills, but older returnees did have the required skills. Many people just did not have an interest in constructing traditional pit latrines.

In addition, in the camp setting, there was no privacy for open defecation but in their places of origin, where populations are sparse and households are far apart, they could easily defecate outside in privacy, for example, in the bush and gardens.

Impact of the slow pace in improving household sanitation

In Gulu District in 2009 the IDP population was 431,000 people with 71,830 households. Only 9% of rural households were able to construct and use latrine by the end of 2009. The rest of the population were using the bush to openly defecate. (2)

As a result of low latrine coverage, there were high incidences of diarrhoea, typhoid, soil transmitted helminths and other sanitation related diseases. High levels of malnutrition were especially common among children, escalated by poor sanitation and hygiene (2). There was also poor water quality: water source monitoring and testing showed high levels of indicator organism implying high levels of contamination.

How those challenges were addressed in Gulu district:

To address the challenge of household sanitation, Gulu District Local Government started a home improvement campaign and home visiting.

– Implementation of home improvement campaign

In home improvement campaigns, meetings were held with health inspectors and health assistants, to develop a workplan with set targets. Selected communities were mobilised and sensitised on the component of an ideal homestead (latrine, drying racks, hand washing facility, rubbish pit, bathing shelters clean compound, animal/bird houses, kitchen and having a separate main house). After this process, an action plan was developed by community members to have all those identified components in place, which guided health extension workers to follow up. This involved meetings with community leaders to discuss how to improve performance.

After every three months a similar campaign was launched in another village. At the end of each campaign, we awarded a bicycle or a radio to the wining household head, those whose home was considered the best against the parameters of ideal homestead. Over two years, however, there was no big change in the status of household sanitation and latrine coverage remained at only 29% for the whole district.

– Implementation of byelaws

These poor results prompted the district to change strategy. In 2011, a report that included statistics on household sanitation, challenges and ways forward to address problems across the 11 sub-counties in Gulu district was presented to the District Council of Gulu district. All sub-counties resolved that there should be byelaws that enforces returnees to construct latrine and other household sanitation facilities. In consultation with the District Lawyer, a draft byelaw was made for all sub-counties, presented to the Sub County Council and Gulu District Local Government Council, who accepted and passed the byelaws.

The penalties for having no latrine at homes were impounding animals like goats, if the household head is a Chairperson on the Local Council of the village, or a chicken, if the culprit is just an ordinary community member without any leadership role. More severe punishment was given to community leaders because they are expected to be exemplary as per declaration signed by all leaders in Uganda called Kampala declaration on Sanitation 1997. To enforce byelaws, a team that composed of sub-county leaders and police officers visited each household every three months. As a result of this, there was tremendous change in household sanitation.

To sustain gains made, the Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) approach was introduced. With support from UNICEF, health inspectors and health assistants were trained to facilitate the CLTS approach. The district then triggered 120 communities with UNICEF’s help and 81 of these communities were declared open defecation free.

This was successful because most natural leaders (community figures who play a vital role in leading the community in improving their sanitation) were elders who remembered life before the camps and they themselves had constructed latrine in their homes. In some cases, communities were mobilising funds to buy their own pickaxes for excavating pits (and incidentally, for burials).

Situation in 2022

Currently, latrine coverage is slightly above the national average and Gulu district was one of the only districts in Acholi sub region that managed to attain latrine coverage of 60% within four years of post-emergency development. Some communities are using traditional pit latrines because of the high cost of materials for the construction of improved latrines. Development partners are supporting construction of improved pit latrines with washable slabs by providing slabs at a subsidized cost.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reducing aid dependency in post-emergency setting can be very challenging and demands instituting and enforcing byelaws through fines. In this case we used byelaws to ensure that returnees construct sanitary facilities and then softened the approach to ensure that they accept and use whatever they constructed. To sustain open defecation free status, approaches like PHAST, CLTS, home improvement campaigns and other behavioral change approaches were used effectively across whole districts.

The author was a lead person in promoting hygiene and sanitation in communities and institutions at the time government and development partners started implementing Peace Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) for post-conflict returnees in Gulu District, Northern Uganda.

References not available online:

1. Gulu District Health Department Annual Report Financial Year 2007/2008.

2. Gulu District Health Department Annual Report Financial Year 2008/2009.

3. Gulu District Health Department Annual Report Financial Year 2009/2010.

4. Gulu District Health Department Annual Report Financial Year 2010/2011.