The global challenge of climate change is greatly affecting developing countries, including Uganda with increased incidences of droughts, floods, erratic rains among many other issues.

When troublesome soil conditions combine with flash flooding, access to sanitation is one of many problems that arise. This is what is facing the people living in the district of Gulu, located in northern Uganda.

According to Langlands classifications (1974), the soil of Gulu consists of ferruginous soil with a high percentage of sandy soils, making it susceptible to erosion. Due to its sandy nature, the soil has a low water retention capacity and a high rate of water infiltration. On a positive note, Gulu district is endowed with vast fertile soils, similar to the neighbouring districts of Orapwoyo in Odek and Adak in Lalogi. This has resulted in very high crop yields.

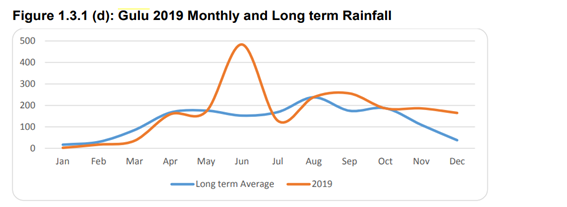

Gulu experiences a climate consisting of dry and wet seasons. The average total rainfall received for 2019 was 1,500 mm per annum. The monthly average rainfall varies greatly, between 1.4 mm in January and 230 mm in August.

Rain, “aluka”, and the knock-on effect on sanitation

At the peak of the rainy season in July and August, Paicho Subcounty in the Gulu District experiences an abnormal heavy downpour, which causes “aluka”, water emerging from underground from everywhere. The pit latrines filled up with running water and their walls collapsed.

At this point, families have resorted to using the nearby bushes for defecation. Here, faecal matter is washed downstream, along with the mud from the roads which are not accessible because of thealuka.

The same stream is shared by both animals and humans. The mud and faecal matter from the dirty roads are washed downstream which is later ‘enjoyed’ by the community and livestock.

This open defecation also usually attracts house flies which contaminate food and fruits. This has led to high prevalence of water-borne diseases among children under 5 and elders in the area. This has put the health and lives of the community at risk.

With ‘aluka’ emerging everywhere, pit latrines fill up and others collapse. This is a problem affecting many people, but the situation of affected families are looked at in isolation from each other. The entire community do not clearly understand that it will indirectly affect all of them, due to the waste washing downstream and contaminating the water.

What needs to happen next?

There is urgent need to raise awareness of these issues within the community, and then support them on how to build modern drainable structures that are capable of withstanding the changing climate.

Here, where there have been heavy downpours, the structures cannot be rebuilt immediately. The affected families will have to wait months until the dry season. Only in the dry season will the digging of the pit be safe. The laying of bricks for the construction process also needs to start in the dry season. As buildings in Paicho are some distance apart from each other, the easiest and the safest place for going to the toilet has become the bush, since the trading center lacks a public facility to be used.

Going forward, construction of a drainable stance latrine in the area is recommended, as seen in schools in other areas. With drainable latrines as seen elsewhere in Uganda, in Imvepi, the substructure can withstand the flooding and it gives a strong foundation to the super structure. Drainable latrines would mean the health and lives of the community would be guaranteed to withstand the ever-worsening rainy seasons in the years to come.