This blog is the fourth in a series of five on the IDS Sanitation Learning Hub supported rapid topic exploration on learning in the WASH sector. For the other blogs in the series:

- No 1: “Learning about learning” in the sanitation and hygiene sector

- No 2: Innovative approaches for inclusive community learning

- No 3: Learning peer-to-peer for sub-national and field level actors

- No. 5: Turning learning and sharing into action at scale

See also the associated Learning Paper and Learning Brief.

So many barriers…

An over-arching feeling that I had when asking the respondents to this study about the barriers that we face for learning and turning that learning to action at scale, was how many there are! It made me wonder how we ever learn effectively and how we ever manage to turn it into widescale action? But somehow, we do, even if it takes time.

Key barriers:

- The diverse backgrounds of personnel, the attitudes of staff, relationships to donors and attitudes of management and human resource personnel, which may bias who gets learning opportunities.

- The turnover of staff, lack of structured learning opportunities and limitations in the commitment by leadership to learning and to prioritising time to learn from communities.

- The use of jargon and language, as well as variations in levels of confidence and ability in writing as well as resistance to reading.

- Gaps in accessibility to information for people with disabilities, ethical risks and risks of doing harm.

- An unwillingness to share on things that have not gone well, or on what are perceived as ‘failures’, with particular concern about admitting these in front of donors.

- An unsupportive enabling environment and gaps in political will.

- Errors, myths, biases and blind-spots in the way we learn, as well as the tension between qualitative and quantitative approaches and understanding of what is acceptable rigour.

- Varied opportunities and resources and variations in the capacity of facilitators and trainers.

- Gaps in the sharing of learning across agencies, with more regular sharing within organisations, and risks that sector actors “follow fashions” when choose what to learn from.

- Huge amounts of information also poses major challenges, as well as some concern over the perception of the proliferation of learning mechanisms.

The issue of the sector still being reticent to learn from ‘failures’, was reflected on as part of the process, with multiple reasons posed for why this happens. This includes fear of donors not wanting to continue to fund programmes going forward, if things that didn’t go so well and if the challenges being faced are shared. Whereas, most donors, would probably prefer to hear directly earlier on, what is not going so well and for programmes to be able to learn and improve going forward, than for issues to appear at a later date. The efforts to increase commitment to being more open about things that have not gone so well through the signing of the Nakuru Accord, is one effort going in the right direction, although more action now needs to be taken throughout the sector.

As part of the learning process, I also read Robert Chambers’ latest book called “Can we learn better?”. I found it a very thought-provoking book, as it made me reflect on my own errors and biases and the myths that I do not always question. Examples of sources of errors and myths are those from power and personal interests, ego, pride and status, propagating findings that conveniently confirm beliefs and extrapolating out of context. Biases and blind spots may be due to ‘strategic ignorance’ when we do not wish to know something, or due to ‘tactics’, such as shelving a report, keeping it confidential, editing it, or limiting its circulation. The delaying of reading or sharing reports as a way to bias our work and delay change, always brings to mind an incident a couple of decades ago when efforts were starting to advocate for increased consideration of gender in the work of our sector. The technical director of a well-known sector organisation, kept the draft of a toolkit for how to practically integrate gender into the organisation’s work on his desk for a year without reading it. I think it never got used, even though a lot of effort had gone into preparing it by a range of staff across the organisation.

Biases can also occur due to spatial focus, such as prioritising visits to communities near to the ‘tarmac’ or the ‘airport’, or only going on visits during certain seasons. There may also be diplomatic biases, in being reluctant to broach sensitive subjects. If we are honest, I am sure that all of us in the sector has experienced, or have been part of propagating some of these practices at some points in our work and careers.

The process of turning learning into action at scale

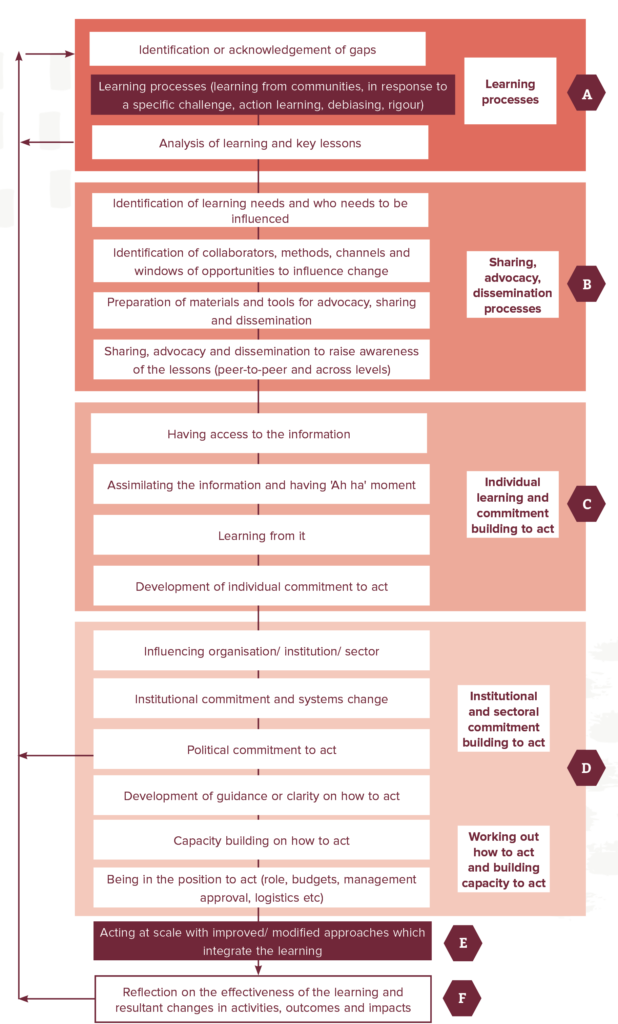

There are multiple factors that affect whether learning can be turned into action at scale. Having access to information on new learning is just a first step. See the figure below which summarises the general order of steps that need to be passed through to turn learning into action at scale.

In relation to the steps outlined in the figure, in reality however: a) the learning processes tend to be iterative, with small spirals, sometimes repeated, rather than one big loop; b) sometimes there is the opportunity to go directly from the learning to direct action, particularly on an individual or small scale basis; and c) sometimes the learning to action process only gets part way through the steps and then faulters, for example if decision-makers cannot be easily convinced that the issue is a priority, or resources not being available, or staff who are committed moving on from their post, with people with different priorities replacing them.

One respondent observed that learning at scale usually only tends to happens when a select group of the key big actors take an issue on board, such as the GATES Fund, the International Resource Centre and the big Banks. They may learn from others, but it is only when they take on the particular perspective, do others follow at scale. Do you agree?

Or do you feel that learning at scale, sometimes happens even when they have not taken on the perspective? I guess the use of CLTS may be one example here where it was taken at scale, without leadership from these bodies; and also efforts on improving menstrual hygiene management (MHM), with none of these players taking a lead role in increasing attention in these areas?

A government actor, emphasised the need to reach the professionals working at local government authority levels and at community leadership levels, as these are the people who are often responsible for turning the learning into action at scale. But that they are often overlooked and we often do not package the learning in formats suited to their needs, including in local languages. It is essential that government are in a leadership position wherever possible from the early stages of learning processes, and supported in a coherent manner by others in these processes, if we are to speed up the use of learning to be able to influence change at scale. See also Blog 3 for more information on this.

Increased coherence in support to government, needs positive and open collaboration between organisations providing that support to strengthen strategies and approaches. A lack of coherence and willingness to work together, can sometimes lead to confusion for governments, being encouraged to move in different directions and use different approaches. It can result in the slowing down of the speed of learning and reduces the effectiveness of scarce resources. There has been an increase in the willingness for collaboration between some organisations in learning, documentation and sharing over the years. This is evidenced by increasing numbers of learning and good practice related documents now being co-published with multiple logos. But I think that many of us are also still aware of attitudes of competition between some organisations and individuals, wanting to be seen as the leaders in particular areas and to have their preferred approaches supported.

And for all of the above, there is a need for increased commitment by leadership within the sector, to take learning seriously, to make structured time for it, to include it in the job requirements of staff working within their organisations and to allocate adequate resources to it happening.

Questions for you

So:

- How effectively do you think your organisation learns and then uses that learning in its own work and to influence others? What barriers do you face in doing this?

- Have you seen other opportunities not mentioned here, that we have for overcoming the multiple barriers and turning our learning into scale more effectively and at greater speed?