Among other programmes, Zambia is rolling out interventions that are aimed at reducing stunting focusing on the first 1000 days of human life (from pregnancy to the second birthday of the child), when action is likely to bring most impact. Efforts are galvanised through the First 1000 Most Critical Days Programme (MCDP) which was initiated after Zambia joined the global network on Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN). The MCDP has been in implementation since 2013. The promotion of WASH is one of the 4 components being harnessed to ensure that there are positive physical, health and cognitive development outcomes in children.

One of the organisations supporting the government’s WASH efforts is the Scaling Up Nutrition Technical Assistance (SUN TA) Project. Working with District WASH committees in 13 districts (Mumbwa, Chibombo, Kabwe, Kapiri Mposhi, Ndola, Kitwe, Samfya, Nchelenge, Kaputa, Luwingu, Mbala and Kasama), the project provides technical assistance to government departments and staff to plan, implement, coordinate, and monitor integrated nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific activities aimed at significantly reducing the rate of stunting among Zambian children under two.

Using all available avenues, the SUN TA WASH program focuses on increasing access to safe water and improved sanitation and hygiene facilities and practices to reduce exposure to environmental pathogens that cause increased risk of diarrheal diseases and intestinal infections. The role that the traditional leaders play in spurring communities into adopting good WASH practices and behaviours has not been fully acknowledged for its support in ending open defecation for all. In this blog I critically unpack traditional leaders’ vital role in implementing Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) programming through a case study from Kaputa, Zambia.

Working with traditional leaders as a CLTS strategy

Zambia is governed by a dual legal system of statutory law and customary law. Chapter 287 of the country’s constitution recognizes the customary role of traditional leaders and gives them the responsibility to discharge their traditional functions in tandem with the Constitution or other written laws.

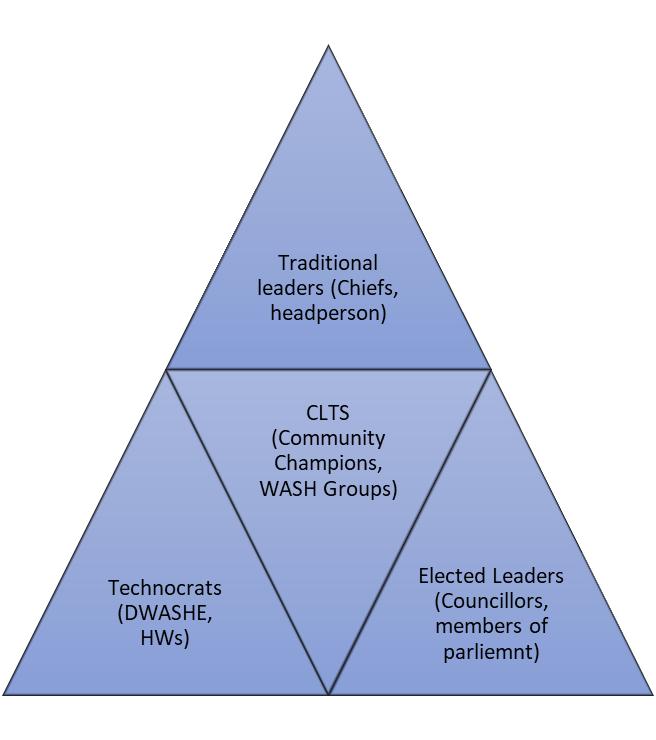

CLTS in Zambia has been using the 3 Rope approach (3RA) as a facilitation management strategy. In this approach, the Traditional Leaders, Civic Leaders and Technocrats have formed a Power Influence Triangle to positively effect uptake of sanitation:

- Traditional Leaders because of their traditional and cultural leadership influence who use their voice as a custodian of traditional values to break limiting or harmful traditional taboos and motivate a toilet revolution in their subjects. They have an effective role as change agents.

- Civic Leaders with their elective and policy influence, play a central role in the communication process between the communities they represent and the Council, reporting back regularly through ward meetings and assisting the community in identifying needs and priority areas of development, which feeds into the municipality’s planning processes.

- Technocrats with knowledge influence from government or private entities, such as the District Water and Sanitation Health Education (D-WASHE) committee and Health Workers (HWs), play a central role as they exercise authority because of their expertise.

Each of these decision makers support CLTS with different viewpoints and have different influence on people and may even emphasise or interpret CLTS’s importance differently. It is important to realize that all three facets compliment and supplement each other. It is essential to increase involvement and engagement each of the three cohorts.

Factors that made working with traditional leaders in Kaputa a success

Kaputa District has two chiefs: Chief Kaputa and Chief Mukupa Katandula.The D-WASHE Committee met them with their respective village headpersons and ignited their interest in taking up leadership in ending Open Defecation (OD). The two chiefs welcomed the initiative and embraced the roles of sanitation ambassadors. They responded positively by conducting follow ups and spot checks alongside their village headpersons. The chiefs’ quick onboarding and support were central in creating sanitation demand, adoption of good practices and creation of peer-to-peer follow ups. The following initiative were employed by these traditional leaders:

- Holding regular meetings with stakeholder like DWASHE committee, Community Champions, and Health Facility staff to review monthly Open Defecation Free (ODF) progress and placed attention on villages that had households without toilets. These meeting were also used to ensure that the community is supporting the CLTS approach and that the commitment to attain the ODF status is supported by the entire community and not just the leadership.

- Through their traditional village level structures, they conducted door-to-door inspections. Using social and health motivators, traditional leadership summoned heads of households who did not construct toilets and asked them to answer why they chose to shame their communities. In Kaputa, like many other African settings, rural families still rely on each other for support and sharing of responsibilities thereby creating safe nets for marginalized households that may fail to meet the demands of the traditional leaders. The aged, poorest and people with disabilities are likely to be kept by other family members or even just close neighbours who would step in to construct toilets. Since CLTS is not externally driven but gives the community leadership to decide what is appropriate for their setting, the community usually have a strong sense of pride and realization of self-potential once ODF is achieved.

- Though Covid-19 created a setback to village triggering which involved gathering a huge number of people, the traditional leadership structures changed the strategy to triggering targeted households that were either lacking toilets or had a missing parameter like handwashing facilities.

Through the two Chiefs’ efforts, the chiefdoms scaled the sanitation coverage to 100% in 2021, thus attaining ODF status in April for Kaputa, and Mukupa Katandula in November bringing the number of ODF chiefdoms in Zambia to 54 from 52. This also helped Kaputa District become the fifth district to be declared ODF after Chiengi, Chitambo, Choma and Vubwi districts. Kaputa will remain as a model district with regards to CLTS especially that all the mass verification and certification was done in the rainy season when traditional toilets are notorious for collapsing due to the heavy rains.

The CLTS challenge in working with traditional leaders

It is believed that no good story is without a challenge. Because of the authority and power that chiefs exert, it is difficult to ascertain if coercive measures or customary laws were used to motivate the behavioural change on sanitation in Kaputa. In addition to customary laws, chiefdoms can come up with their own by-laws, unknown to outsiders, requiring subjects to construct toilets, with associated penalties for defaulters. These by-laws are crucial to achieve national sanitation targets. Any form of coercion, of course, goes against the very essence of CLTS. This is the challenge that CLTS and the sustainability of ODF has in Zambia, and elsewhere.

How then do we ensure equality and non-discrimination (EQND) within the CLTS process? Should traditional leaders and any other implementors of CLTS be encouraged to develop context-based strategies that ‘do no harm’ but still include clear fines and penalties for defaulters? If community problems require community solutions, how do external technocrats ensure ethics are upheld? And who defines these ethics?

Conclusion

For progress in any society, there must be subordination of individual interests to the collective interests. However, there must be a balance as every precaution must be taken to ensure that people are not put at greater risk or left worse off through sanitation intervention being promoted. It is clear that the two traditional leaders played a valuable role in the CLTS process and achieving ODF status in Kaputa. However, there is a need for more transparency around the methods they used to motivate people to build latrines and change their behaviours. It would be interesting hear from other sanitation practitioners if these reflections and findings apply to traditional leaders in other contexts.

In a follow up blog, I intend to share findings on how subjects in Kaputa feel about traditional leaders’ role in CLTS. This will be alongside feedback from a discussion with the ministry responsible for sanitation and national CLTS leaders on who holds traditional leaders accountable in CLTS programming .