In 2021, traditional leaders in Kaputa district in Zambia were instrumental is ensuring that their jurisdiction attained Open Defecation Free (ODF) status. You can read about this in my first blog Traditional leaders’ role in sanitation: Lessons from Kaputa, Zambia. However, it also revealed a dilemma: because of the authority and power that chiefs exert, it was difficult to ascertain whether coercion or personal obligations underpinned the behavioral change on toilet construction and use in the community that translated into the ODF status.

In this follow-up blog I investigate this tension through discussions with traditional leaders, Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) coaches and community members from Kasama, Kaputa and Mansa districts. I share findings on how subjects* and other stakeholders in Kaputa and other districts feel about traditional leaders’ role in CLTS. I also present feedback from a discussion with staff from the Ministry of Water Development and Sanitation (the ministry responsible for sanitation) and national CLTS leaders on who holds traditional leaders accountable in CLTS programming.

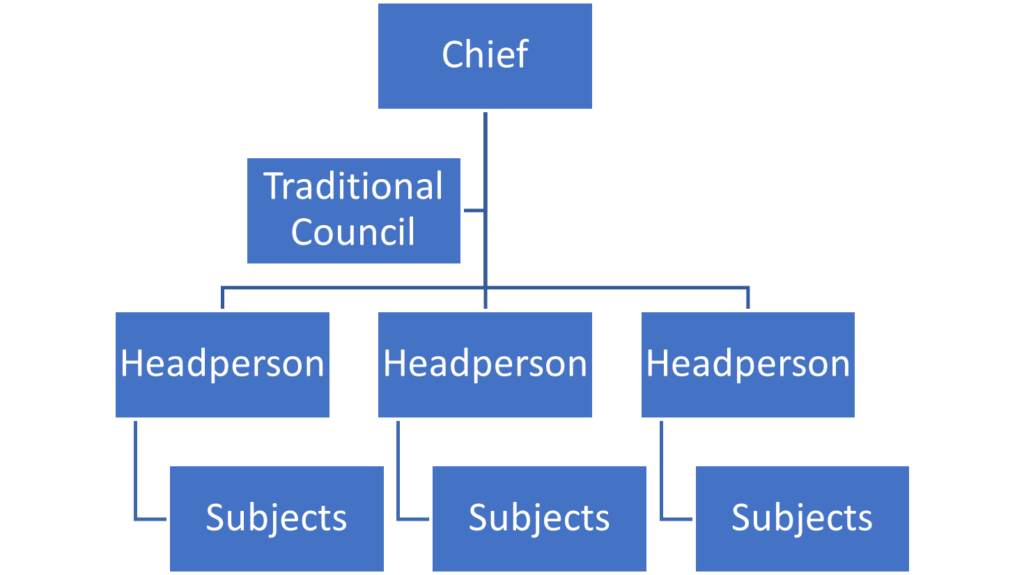

*In this context the term subjects refers to people that a traditional leader has jurisdiction over. It is widely used in Zambian legislation.

Traditional leaders’ approaches for sanitation demand creation

At village level, headpersons are invited by the chiefs and asked to facilitate the construction of latrines in their villages. Like CLTS facilitators, chiefs and headpersons facilitate communities to analyse their own sanitation practices. During this triggering process, communities come to the realisation they are essentially eating each other’s shit, resulting in communities taking action to become open defecation free. In my interviews, a number of methods were identified to encourage communities to change their sanitation behaviours:

- Use of language: To challenge taboos and set a tone for the entire communities in his jurisdiction, one of the chiefs interviewed claimed to be actively involved in ‘talking about shit’ as a facilitator in CLTS triggering and monitoring.

- Stakeholder meetings: In my discussions, both traditional leaders and their subjects regarded ‘chiefdom review meetings’ as significant platforms used by headpersons to report to chiefs on sanitation coverage. These meetings are conducted at the chief’s palace where every headperson is expected to give an account of sanitation in their respective villages. The chief also visits individual villages at least three times per year to appraise compliance and adherence.

- Sanctions: Sanctions have reportedly proved effective for people unwilling (not unable) to construct or use a latrine. Defaulters were charged K50 at village level by their headperson. Stubborn ones were taken to the chief’s palace where they were charged a goat or made to work in a communal field called ‘Umulima Cipuba’ – a farm cultivated by village members labeled as indolent and un-cooperative. Chiefs in Chienge districts employed this same practice when supporting the attainment of ODF in 2015.

“Other forms of punishment would be meted where you are expected to work at the Palace the whole day doing drudgery works like drawing water, washing, cleaning the surroundings. Now imagine a grown-up man like me – married with children – doing such work which I don’t even do in my own household? Better I comply with a directive which by and large benefits me and my household than wait just to endure such humiliation” – John from Kaputa (not real name)

- Incentives: The approaches used facilitated self-awareness and tried to motivate village members. The cleanest household in a village was awarded a watch or phone bought using the fines collected from defaulters. Awards were also given to the cleanest village. The Acting Senior Chief Kaputa said his village headpersons did not ask for incentives when he allocates them assignments. Being a community leader was an incentive enough.

Mechanisms for voicing concerns against traditional leaders

During the CLTS process, care should be taken to ensure people are supported and encouraged, rather than bullied into changing their behaviour (House and Cavill 2015). Clear procedures to address community members’ grievances are needed. The grievance procedure in the traditional court system gives an opportunity for anyone to anonymously report the village headpersons to the chief. The chiefs in Kaputa run a radio program titled Community Concerns which also gives opportunity to people to voice their concerns.

“Traditional leaders are held accountable by what is stipulated in the Chiefs Act, the House of Chiefs (an elected body of chiefs that provides coordination and operational support to traditional leaders throughout the country), the Royal Council and by the Local Authority.” – National CLTS Technical Advisor

The law also states that punishing people is always the last resort for chiefs.

“These enforcement mechanisms aren’t about punishing people per se. Rather, they are a way to prevent the lack of cooperation that allows truancy to go unpunished which could lead to disorder. For this reason, chiefs are compelled to act on the reported cases and penalize defaulters.” – Acting Senior Chief Kaputa.

However, it is important to note that the Village Act Cap 289 empowers chiefs to incur penalties on defaulters and non-compliance on village related developmental initiatives, with the support of the police and Local Authority.

“But if not comfortable with the traditional leader or just not satisfied with the judgement, the aggrieved individual can go to police or to court. In this village, our leader is hardworking and would even go to the extent of punishing someone to facilitate behaviour change on things like child marriages, GBV and failure to take children to school. Which is good.” – Zeli (not real name)

For traditional leaders, canvassing popular support for any decision that will benefit the majority – like demand creation of sanitary facilities – is a hallmark of their leadership. This is consistent with their constitutional provisions in promoting development through the upholding of people’s rights and equality before the law.

Mainstreaming gender and social inclusion

Like any other CLTS facilitator, chiefs were trained not only in CLTS but also their roles and responsibilities in the national developmental agenda. The trainings also emphasised their critical influence on people as traditional leaders and how they can use that influence to safeguard the rights and dignity of the marginalised populations. Care is taken to ensure people who cannot afford, or who are unable to construct, a latrine are supported. This is often through the extended family, which is very common, as ‘relatives’ family can run into hundreds and mainly the entire villages are made up of people that are somewhat related. This setup ensures that the vulnerable members of society are protected and supported as the responsibility of toilet construction may be placed on other family members with energy. It also ensures they are not subject to sanctions, which are targeted at those unwilling to change their behaviour:

“Our communities are tightly knitted where the marginalized and those who can’t construct toilets on their own are already known and are usually helped using other means as doing nothing can also be retrogressive. How do we deter others from doing the same wrongs without effecting fines and penalties on defaulters? Therefore, without any disability or some type of extenuating circumstances, everyone is expected to construct their toilets and participate in any other developmental activities in the community.” – Chief Mabumba

Zambia, being a member of the United Nations, adopted the Resolution 15/9, which recognises the right to sanitation as a human right. Thus, the government works with traditional leaders towards realising this right, who have a responsibility to identify and help people in their jurisdictions that can’t construct a toilet on their own. Traditional leaders are closely involved in the entire CLTS programming starting with their role in the Zambia Open Defecation Free Strategy 2030 to learning events like the Sanitation Summits and WASH commemorative days.

I think the Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI), Do No Harm (DNH) and Equality and Non-Discrimination (EQND) approaches are understood and practiced within the spirit of Ubuntu which is prevalent in rural settings. Ubuntu is the correct behaviour in the sense of a person’s relations with other people. A person with ubuntu knows their place in the community and are consequently able to interact positively with other individuals. In villages, one’s progress is contingent on the progress of others. Hence failure to construct a toilet by a community member frustrates the entire community’s aspiration – a butterfly effect. Therefore, EQND shouldn’t be looked at in isolation but in relation to the prevailing laws and contexts to avoid contradicting entitlements with rights.

Conclusion

The discussions didn’t yield a conclusive rebuttal if positive behavioral change towards sanitation and hygiene was a result of intimidation or personal obligations. I think it was an outcome of both. Thus, it is my opinion that EQND and DNH should take into consideration two important aspects: 1) the prevailing context including the different laws that recognise the established authorities and how they relate with their subjects, and 2) the collective interests of facilitators of CLTS. Communities usually make their own by-laws on sanitation and hygiene during the CLTS triggering meetings, and the traditional leaders are mandated with the enforcement of such laws. The conversations on using traditional leaders in pushing for sanitation coverage can be juxtaposed with the debate on the ethicality of using shame, fear and disgust in CLTS triggering. This is because one person’s refusal to construct a toilet affects the collective’s right to live in a clean and safe environment. These are the nuances. Thus, I would conclude by recommending that intensive research be conducted to determine the specific potential risks and harms of using traditional leaders in CLTS.

Tribute: Chief Mabumba, who not only positively participated in the interviews for the blog but was also supportive of sanitation and hygiene interventions in his chiefdom, died on 22nd November 2022 prior to the publication of this blog. He was, until his death, the Chief in Mansa and a representative of the Luapula Provincial Chiefs Council to the House of Chiefs. He used his leadership position to challenge cultural norms and behaviors that were incongruent with development aspirations. A true partner of development who wanted to see the lives of his people improve, and the only way his people can honour him is to sustain the sanitation gains that he facilitated. MHSRIP.

A note from the Sanitation Learning Hub:

This blog highlights the important role of traditional leaders in enforcing by-laws through igniting personal obligation to collective health and dignity interests, however it also suggests that coercion is used alongside this. Punishment is said to be focused on those who are unwilling to build and use toilets, rather than those who are unable. We would like to highlight that with this approach there is still a risk of undue pressure being placed on potentially vulnerable and marginalised community members to build latrines to meet targets. There are various practical resources available giving suggestions for how issues such as gender, equity, social inclusion, and sustainability can be integrated into CLTS programming, including:

- Equality and Non-Discrimination (EQND) in Sanitation Programmes at Scale (Part 1 of 2)

- Support Mechanisms to Strengthen Equality and Non-Discrimination (EQND) in Rural Sanitation (Part 2 of 2)

- CLTS and the Right to Sanitation

Find out more on our Community-Led Total Sanitation page.