Accelerating progress in rural sanitation towards SDG 6 is possible. India’s Swachh Bharat and Nepal’s Sanitation and Hygiene Master Plan are examples of how a politically prioritized and well-funded effort can make it happen. A significant body of research provides lessons on how to maximise the impact of rural sanitation programmes. But are we embedding these lessons in new sanitation programmes? Not yet.

The Sanitation Learning Hub, SNV, UNICEF, USAID, WaterAid, and the World Bank with the support of USAID/WASHPaLS came together in November 2021 to start to address this. Building on the 2019 Rural Sanitation Call to Action principles, we organised an online workshop to discuss the latest evidence and experiences of area-wide rural sanitation and related hygiene programming. We tried to capture key lessons that, if embedded in mainstream rural sanitation practice, will help accelerate progress. The lessons are structured around six themes, and presented in this blog series:

- Government-led programming

- Sustaining gains

- Strengthening markets

- Reaching the most vulnerable with subsidies

- Challenging contexts and climate change

- Area-wide outcomes and data

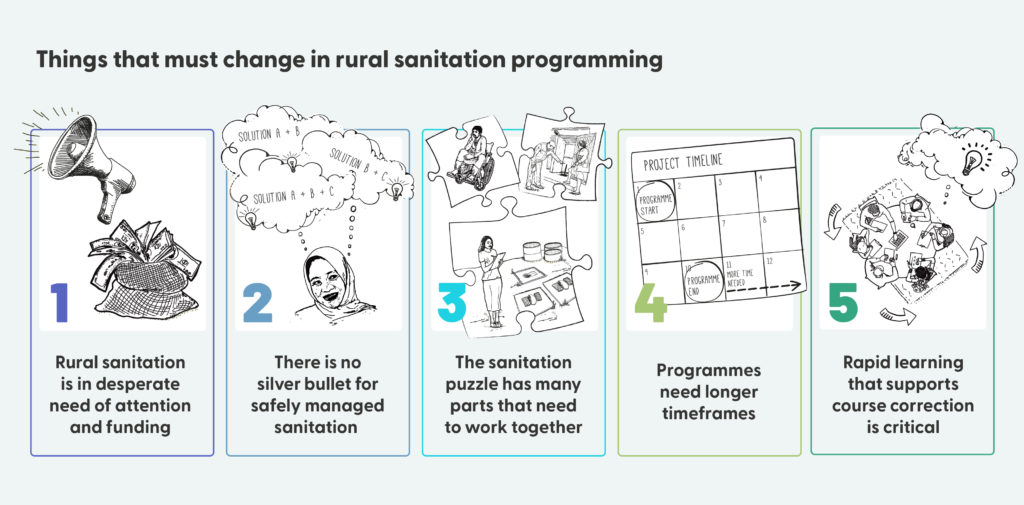

There were also five overarching messages, which speak to what needs to change more broadly in how we fund, design and implement rural sanitation. You can see the headline message in this infographic, but I’d recommend you check out the workshop report to get all the details and case study examples.

This blog focuses on scaling up rural sanitation within challenging contexts and a changing climate.

Some readers may recall, while we achieved the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target for water five years early in 2010, we missed the MDG target for sanitation. At the conclusion of the MDGs, the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) estimated that nearly a billion people globally still practiced open defecation.

That energised the sanitation sector and we successfully advocated for sanitation to be recognized as a basic human right, with a call for “sanitation for all”. Around the same time, we were seeing an evolution in programming from a focus on infrastructure and hardware subsidies to behaviour change interventions using grass roots community mobilization, market-based approaches, and more targeted subsidies.

According to the JMP, between 2015 and 2020 the population practicing open defecation decreased by a third, to under 500 million people and 85% of this drop was in rural areas. Once we started coming together – governments, international organizations, civil society, the private sector, academia, etc. – and stopped being afraid to talk about “shit”, the world started to see real progress in sanitation.

More recently, however, a refocusing of efforts toward the intractable issues in the sector that still need attention. Investment for rural sanitation remains insufficient and more recently, the trend seems to be taking a downward turn.

The SDG ambition of universal access to improved sanitation has not been accompanied by the necessary investment as donors and governments prioritise instead sectors with more straightforward return on investment like the energy sector (WaterAid, 2021). We need to double down on sanitation’s unfinished business – reaching the poorest and most marginalized and addressing climate impacts on sanitation.

Though successful at reaching large numbers, current programs are not delivering the results needed in a range of challenging contexts. These include the poorest and most marginalized, but there are also those who are deliberately excluded. Some have entrenched attitudes and social beliefs towards their sanitation and hygiene practices or have lifestyles/livelihoods (including pastoralism, fishing communities, etc.) that make it difficult to change. Some simply live in tough physical environments while others are in fragile contexts.

Often these categories intersect – for example, some pastoralist communities in Kenya live in arid areas with water scarcity and unstable soils with insecurity, extreme poverty and social beliefs constraining toilet access and use (USAID 2021). Limited practical guidance has been found on ways to implement programs in these contexts at the speed and scale required to ensure safely managed sanitation for all by 2030.

In addition, the impacts of climate change on sanitation access, systems, services, and infrastructure are already being felt, undermining decades of progress in rural sanitation with the greatest impact on these people who are hardest to reach. In a recent case study of our program in Bangladesh, the biggest hurdles to reaching everyone with climate resilient sanitation services identified was community remoteness, repeated bouts or lasting climate events, difficult ground conditions, and limited finances for households to afford the appropriate sanitation solutions. (UNICEF, 2022).

The key learnings and messages from research and ongoing initiatives include:

- encouraging governments to lead coordination efforts within their jurisdictions, using a consortium approach at the local level that could combine forces and datasets across sectors (health, education, water, sanitation) and other social protection efforts to ensure no one is left behind (Kohlitz and Iyer 2021)

- increasing programme budgets – acknowledging that service provision in challenging contexts is likely to cost more money

- providing more nuanced guidance on support mechanisms, especially in areas where both the costs of safely managed sanitation and extreme poverty are high

- strengthening climate resilience in sanitation policies, plans, budgets, and services for accelerated progress on SDG 6.2.

- supporting governments on identification and awareness creation on all the available climate finance options and how government in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) can access these funds and mobilize additional domestic resources for sustainable funding of equitable climate resilient safely managed rural sanitation.

- doubling efforts on evidence generation and dissemination on the impact of climate change along the whole sanitation service chain for sustained advocacy and effective planning of appropriate approaches and interventions.

As part of the efforts of accelerating progress to safely managed sanitation services, UNICEF is developing a Sanitation Game Plan aimed at supporting governments to achieve safely managed sanitation for both rural and urban areas through direct service delivery and systems strengthening. UNICEF is also working with sector partners on global advocacy and capacity development on climate resilient sanitation.

We are also currently developing guidance for rural sanitation in challenging contexts with The Sanitation Learning Hub and WaterAid.