In 2015 SLH published ‘Making Sanitation and Hygiene Safer: Reducing Vulnerabilities to Violence’, a very useful resource written by Sarah House and Sue Cavil highlighting violence that mainly women and girls face in accessing sanitation and hygiene and practical recommendations to tackle this.

A lot has happened in five years in terms of global crisis, WASH programming approaches and understanding of gender within the sector. In this blog I provide an overview of this still relevant resource and make suggestions for new dimensions and ideas that might be considered to bring it up to date in 2020. I was inspired to write this blog to mark International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on November 25th, drawing attention to important links between between Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) and Gender-Based Violence. (These are just my musings and not the thoughts of the authors.)

Making Sanitation and Hygiene Safer in 2015 – an overview

Concerns over safety, privacy and dignity when using sanitation and hygiene facilities, for women and girls especially, can lead to them not accessing latrines at all or only going during hours of darkness. Open defecation typically occurs in unsafe locations, for example, behind bushes or in open bodies of water. Also if a woman or girl waits until dark to defecate, they can face harassment, abuse and the threat of rape.

Poor design and siting of latrines or hygiene facilities are not the root cause of gender-based violence (GBV), but they can contribute to increased vulnerabilities to violence, as well as fear of violence, which can affect how facilities are used by different people, and also the ability of communities to become and remain open defecation free (ODF).

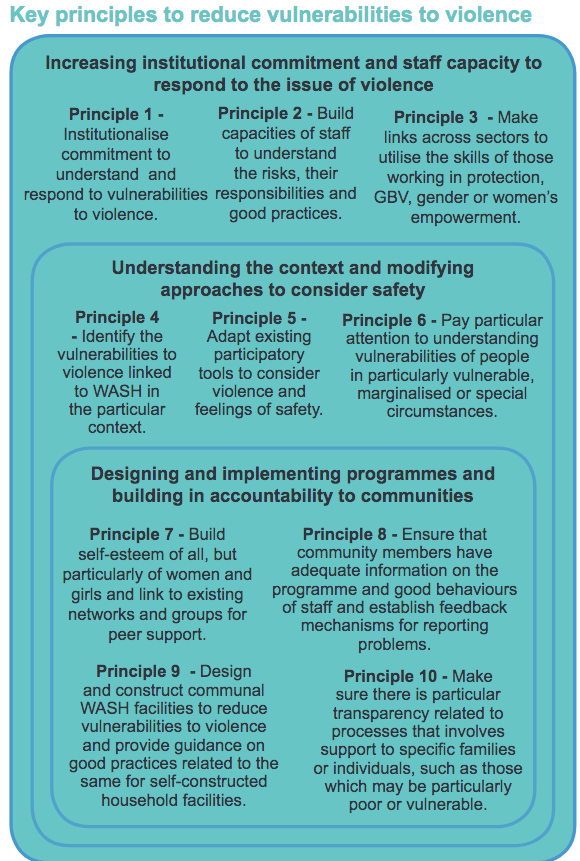

The resource provides a still very relevant set of principles for making simple modifications to programme and organisational processes can help ensure that Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) methodologies contribute most effectively to the overall reduction in vulnerabilities to violence.

It also points out areas in which Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) methodologies, if not used skilfully with awareness and care, can create additional vulnerabilities – for example, as a by-product of community pressure to reach ODF status. It looks at good practices within organisations to ensure that practitioners know how to design programming to reduce vulnerabilities to violence and to ensure that sector actors also do not become the perpetrators of, or face violence.

Five years on – what’s new?

Below I outline what I think are some of the key developments leading up to and in 2020 that could be considered in relation making sanitation and hygiene safer to reduce vulnerabilities to violence.

COVID–19 and increased violence against women and girls (VAWG)

This year, International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women (25 November) focuses on the increase of VAWG, especially domestic violence, around the world, since the outbreak of COVID-19. The pandemic has exacerbated key risk factors for VAWG, such as food shortages, unemployment, economic insecurity, school closures, massive migration flows and the threat of civil unrest.

It is important to consider how existing vulnerabilities to violence in accessing WASH facilities have increased for women and girls (and others) during the pandemic and provide guidance on how this can be rapidly addressed by the WASH sector. For example, what have been the various experiences of women and girls using shared latrine facilities during the pandemic? Have they reverted to OD when public latrines have been closed due to COVID-19 restrictions? How have women with extra challenges, for example, women who are homeless, live with a disability and/or incontinence, experienced COVID-19 restrictions on WASH?

This article published in India talks about increased pressure on getting water for handwashing, especially for households under strict lockdown who don’t have a water connection, this can mean women and girls having to collect water after dark. It also highlights the problem of women and girls spending more time queuing for water and the increase in verbal and physical harassment as a result. This UNICEF report mentions adolescent girls having their period for the first time during the pandemic and being unable to access products and wash them (pg4).

The rate of change and the complexity of the challenges the sanitation and hygiene sector faces in reaching SDG 6.2 are considerable and increasing. Over the past few years, the Sanitation Learning Hub has responded to this by broadening its focus to include an array of community-focused approaches, as an innovator within the sector. The Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) approach still plays an important part but is no longer the sole focus of the Hub, and a new, more encompassing name, the Sanitation Learning Hub, promotes and reflects this change in focus. Going forward, the thrust of the Hub’s work will be to promote timely, rapid and adaptive learning and sharing, alongside honest reflections of what works and what doesn’t.

Our Rapid Action Learning (RAL) approaches need to be considered when addressing GBV in WASH in diverse contexts.

It is vital to think about who we’re not talking about enough and who is in danger of being left behind in the drive for sanitation and hygiene for all. It seems we have a long way to go, in terms of including, among other groups, sexual and gender minorities in our work on sanitation and hygiene.

This is a challenging topic to address. In 13 countries, it’s against the law to be transgender. Elsewhere, sexual and gender minorities face harassment, violence and ridicule when accessing toilets.

Water for Women, in collaboration with Edge Effect, have developed a guidance note on ensuring access to appropriate WASH services and facilities for people from sexual and gender minorities (SGM) groups, who are even more marginalised during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a forthcoming blog, Alice Webb sets out progress so far in the WASH sector, powerful taboos and stigma that still needs to be overcome and first steps towards achieving this – including ideas for changing our language in the sector around how we talk about issues faced by sexual and gender minorities.

Gender transformative approaches to programming aim to transform the power structures that underlie unequal gender relations and norms. Empowering marginalised women and girls to come into the public domain, share their perspectives, take on leadership roles, set political agendas and form movements is central to this approach. Working with men and boys as allies and champions of change is also vital to challenge and transform dominant social, economic and political structures that perpetuate gender inequality. Transformative approaches also aim to understand how gender inequalities intersect with and compound other inequalities, striving for more complex and nuanced programming.

This blog ‘Nine ideas for gender transformative WASH programming’, sets out ideas for WASH practitioners on how to include these approaches in programming.

Gender issues and dynamics affect everyone individually, every day. Our judgements and decisions around gender and sexuality are often so deeply ingrained that we make them unconsciously. It is vital that WASH practitioners recognise and address their own conscious and unconscious gender and sexuality biases. Learn more in this article, ‘A call to action: organisational, professional and personal change for gender transformative WASH programming’.

It is important to understand women’s and girl’s specific WASH priorities and vulnerabilities to violence in attempts to reverse slippage. If toilets are not considered to be safe and private, especially by women and girls, then it is likely they will slip back to open defection which can further increase vulnerabilities to violence. There is widespread recognition that slippage of open defecation free (ODF) status is a challenge to sustainability across many programmes and contexts.

This guide from our Frontiers of Sanitation series, ‘Tackling Slippage’ provides examples of field experience of slippage and the actions taken to reverse it.

In India, the SBM nationwide campaign has resulted in the widespread construction of latrines across the country. Yet many women still don’t see the benefit of using a latrine over OD. Read this blog about women’s expereinces of latrine use and slippage in rural India and what more needs to be done.

Thanks and credits

I’d like to extend thanks to the authors of ‘Making Sanitation and Hygiene Safer: Reducing Vulnerabilities to Violence‘ – Sarah House and Sue Cavil – for their work in creating this important resource. The content of this publication has been based on the learning gained during the development of the ‘Violence, Gender and WASH: A Practitioner’s Toolkit’ which was co-authored by Sarah House, Suzanne Ferron, Marni Sommer and Sue Cavill.

The toolkit was funded by the Department for International Development (DFID) through the Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) Consortium and co-published by 27 organisations. Many individuals and organisations across a range of disciplines contributed to the development of the practitioner’s toolkit. Please refer to the Briefing Note 1 for the full set of acknowledgements. Please refer to Toolset 8 for the full list of references used during the development of the toolkit.

Final note: I’d just like to reiterate that the suggestions presented are just my musings on the issue and do not reflect the thoughts of the authors.